28. Juni -

10. August 2025

Gmunden.Photo 2025

28. Juni - 10. August 2025

im KunstQuartier Stadtgarten Gmunden & Kunsthaus Blaue Butter

Öffnungszeiten:

Di.-So. 13:00-19:00

(Mo. geschlossen).

Eintritt 5€.

Die gmunden.photo widmet VALIE EXPORT (geb. 1940 in Linz, lebt in Wien), die im Mai ihren

85. Geburtstag gefeiert hat, im Sommer 2025 eine Einzelausstellung – die erste in dieser

eigentlich als Gruppenausstellung konzipierten Reihe. Die Schau, die im Kunstquartier

Stadtgarten und im Kunsthaus Blaue Butter in Gmunden zu sehen ist, würdigt das visionäre,

radikale und hochpolitische Werk dieser Pionierin der feministischen Kunst und

Performance-Art.

VALIE EXPORTs Schaffen ist seit mehr als fünf Jahrzehnten geprägt von der kritischen

Auseinandersetzung mit Gesellschaft, Identität, Körper und Medien. Erstaunlicherweise hat

es nicht an Aktualität eingebüßt: Arbeiten wie das TAPP- UND TASTKINO, bei dem die

Künstlerin Menschen auf der Straße aufforderte, in eine Box an ihrem Oberkörper zu greifen

und ihre Brüste zu berühren, hinterfragen den Status des weiblichen Körpers in

Gesellschaft und Medien und sind erschreckenderweise heute genauso relevant wie Ende der

1960er-Jahre. In ihrem Werk verbindet sich der kritische Impetus mit dem Nachdenken über

Medien und der Fähigkeit, technikübergreifend zu arbeiten.

Die eigens für Gmunden konzipierte Ausstellung „VALIE EXPORT. Ins Auge stechen“ zeigt

einerseits EXPORTs bekannteste Arbeiten. Andererseits bietet sie durch die Präsentation im

öffentlichen Raum und den innovativen Umgang mit den Bedingungen vor Ort auch die

Möglichkeit, Werk und Wirken der Künstlerin in einer ganz neuen Form und Umgebung zu

betrachten. Das Studio VALIE EXPORT und ich haben dafür zusammen ein Konzept erarbeitet,

das die Frachtcontainer, die seit mehreren Jahren als „Ausstellungsräume“ für die

gmunden.photo genutzt werden, als gestaltende Elemente einbezieht.

Bei der gmunden.photo, die heuer zum fünften Mal stattfindet und sich in den letzten

Jahren zum sommerlichen Fotografie-Hotspot entwickelt hat, kann man Arbeiten aus allen

Schaffensperioden der Ausnahmekünstlerin entdecken und die ungebrochene Relevanz ihres

künstlerischen Auftrags begreifen.

Lisa Ortner-Kreil

gmunden.photo is dedicating a solo exhibition this summer—the first in this series

originally conceived as group exhibitions—to VALIE EXPORT (born 1940 in Linz, lives in

Vienna), who celebrated her eighty-fifth birthday in May 2025. The show, which will be on

view at Kunstquartier Stadtgarten and Kunsthaus Blaue Butter in Gmunden, is a homage to

the visionary, radical, and eminently political work of this pioneer of feminist and

performance art.

For more than five decades, VALIE EXPORT’s work has been informed by critical explorations

of society, identity, the body, and the media. Surprisingly, it has not lost any of its

topicality: works such as TAP AND TOUCH CINEMA, in which the artist invited people on the

street to put their hands into a box mounted on her upper body and touch her breasts,

interrogate the status of the female body in society and the media and, shockingly, are no

less relevant today than they were in the late 1960s. Her work combines a critical impetus

with media reflection and the ability to work across different technologies.

Conceived especially for Gmunden, the exhibition “VALIE EXPORT: Hitting the Eye” on the

one hand is a survey show of EXPORT’s best-known works. On the other, the presentation in

the public realm and the innovative take on the specifics of the venue also offer an

opportunity to view the artist’s work in an entirely new form and environment. The studio

of VALIE EXPORT and I have collaboratively developed a concept that engages as design

elements the freight containers used for years as “exhibition spaces” for gmunden.photo.

Taking place for the fifth time this year, gmunden.photo, which has meanwhile developed

into a summer photography hotspot, lets viewers discover works from all creative periods

of this unique woman artist and get an understanding of the undiminished relevance of her

artistic mission.

Lisa Ortner-Kreil

Lisa Ortner-Kreil (LOK):

Liebe VALIE EXPORT, vielen Dank für die Möglichkeit zum Gespräch. Beginnen wir mit

Gmunden. Es ist ja eine Open-Air-Ausstellung, und das Areal des Stadtgartens, also der

ehemaligen Stadtgärtnerei, oberhalb des Sees ist von einer sehr schönen landschaftlichen

Kulisse umgeben. In den letzten Jahren habe ich mir bei der Zusammenarbeit mit

verschiedenen Kunstschaffenden aber immer wieder gedacht, dass auch die Wildheit des

Stadtgartens eine besondere Anziehungskraft hat. Ich möchte Sie zu Beginn gerne fragen,

ob Sie eine persönliche Beziehung zu Gmunden haben.

VALIE EXPORT (VE):

Ja, insofern, als ich immer ins Salzkammergut fahre zu meiner Schwester, nach Bad Ischl

und Strobl. Ich fahre meistens mit dem Auto, und Gmunden ist dann so eine Stadt, wo man

aussteigt und einen Kaffee trinkt und spazieren geht oder einen Imbiss einnimmt. Gmunden

ist für mich ein schöner Ort – der eine Geschichte hat, wie das ganze Salzkammergut, das

muss ich jetzt nicht extra erwähnen, auch eine sehr tragische und traurige Geschichte.

Trotzdem herrscht dort eine gewisse Aufbruchstimmung. Das macht sicherlich der See aus.

Man kann auf der Esplanade gehen und hat entweder das Ruhige vom See oder – bei Wind –

das etwas Wildere vom See. Man kann auch bei Regen und Sturm in Gmunden spazieren gehen,

die Häuser schützen ein bisschen, weil es eng ist, aber der Hauptplatz ist ganz frei.

Und dann ist man diesen Naturgewalten nicht nur körperlich ausgesetzt, auch das Sehen

ist ihnen ausgeliefert. Ich empfinde das immer so, als könnten diese Gewalten in meinen

Körper und meine Wahrnehmung eindringen.

LOK: Nicht umsonst waren Gmunden und das Salzkammergut immer schon ein

Anziehungspunkt für Künstler:innen, und in den letzten Jahren haben sie sich als

Kulturstandort durch die Salzkammergut Festwochen und die gmunden.photo stark

weiterentwickelt. Ich finde diese körperliche Wahrnehmung interessant, die Sie

angesprochen haben – was der Ort mit dem Körper macht. Der Körper, die Wahrnehmung und

die Sprache sind seit den 1960er-Jahren drei Pfeiler Ihrer künstlerischen Arbeit. Bei

der Vorbereitung der gmunden.photo habe ich festgestellt, dass Ihr Werk einerseits diese

bekannte toughe, manchmal auch gewaltvolle Note hat und sich andererseits in einem

lyrischen Spannungsfeld bewegt, sehr sprachorientiert und poetisch ist. Es ist also hart

und zart zugleich. Wie hat sich Ihr Blick auf das eigene Werk über die Zeit verändert?

Sie feiern ja in diesem Jahr Ihren 85. Geburtstag.

VE: (Lacht.) Ja, das ist richtig. Der Blick auf die Arbeiten, das ist eine Frage,

die schwer zu beantworten ist, denn die Arbeiten sind einmal entstanden und da hatte ich

meine Intention, meinen Blick, meinen Ausdruckswillen. Diesen Ausdruckswillen und

Darstellungswillen habe ich immer noch. Er ist vorhanden, wenn ich die Arbeiten sehe.

Ich erinnere mich zum Teil, warum und aus welchen Wurzeln sie entstanden sind, das

ändert sich nicht. Aber der Blick auf sie ändert sich natürlich, schon durch die

Veränderung der Gesellschaft. Weil ich mich frage: Was habe ich dazumal aufgegriffen von

der Gesellschaft, von der regierenden Gesellschaft, von der politischen Gesellschaft,

von der kulturellen Gesellschaft? Habe ich das Richtige aufgegriffen? Dieser

Auseinandersetzung stelle ich mich auch heute noch. Aber natürlich nicht täglich und

nicht intensiv, sondern vor allem wenn ich die Arbeiten sehe. Meine Arbeiten sind meine

Lebensbegleiter, sie begleiten mich mein ganzes künstlerisches Leben lang. Wenn ich sie

anschaue, sehe ich natürlich auch, wie mein Leben sich verändert hat. Und wie sich die

Konnotationen meiner Arbeiten verändern und anpassen. Das ist eigentlich auch das Schöne

an Kunstwerken – dass man sie nicht nur in einem Augenblick, in einem Zeitraum

wahrnehmen, interpretieren und aufnehmen kann, sondern sie sich auch verändern; dass man

die Vergangenheit sieht, die Zukunft und vor allem die Gegenwart durch das Betrachten im

Moment.

LOK: Diese Veränderung über die Zeit hat natürlich auch mit gesellschaftlichen

Veränderungen zu tun, die sich auf die Wahrnehmung der Werke auswirken. Andererseits

finde ich die Aktualität Ihrer Arbeiten geradezu erschreckend. 1968 haben Sie

angefangen, Ihre radikalen Ideen vor allem zur Rolle der Frau in der Gesellschaft

umzusetzen. Die Fragestellungen von damals sind heute immer noch aktuell, was einiges

über den Zustand unserer Gesellschaft und eines Feminismus aussagt, der sich zwar

weiterentwickelt hat, aber auch von Rückschritten bedroht ist, der wegen der politischen

Umstände keine kontinuierliche Vorwärtsentwicklung erlebt.

VE: Ja, das ist richtig. Die Politik macht immer wieder Rückschritte und dadurch

haben die Arbeiten auch heute ihre Bedeutung. Beim Feminismus sieht man das sehr gut. Es

haben sich sicher manche Sachen geändert, durch den feministischen Gedanken, durch die

feministische Kraft. Aber viele Dinge sind noch genau so, wie sie früher waren, vor 20

oder 30 Jahren, weil die Gesellschaft viel Zeit braucht, bis sie etwas akzeptiert und

sich verändert, und weil sie vom politischen Weltgeschehen abhängig ist. Wir leben nicht

isoliert und die Kunst lebt auch nicht isoliert. Die Kunst war nämlich immer ein

Ausdruck der Kultur. Da braucht man nur in der Kulturgeschichte zurückzugehen. Es hat

auch viel mit Religion zu tun gehabt – sie hat der Gesellschaft repressive Regeln

auferlegt. Und damit hat sich auch die Kunst beschäftigt.

LOK: Weil es in Ihrer Biografie – Sie sind ja gebürtige Oberösterreicherin – und

auch mit dem VALIE EXPORT Center in Linz und jetzt der gmunden.photo diesen starken

Oberösterreich-Bezug gibt, möchte ich Sie fragen: Wie empfinden Sie vor den Unterschied

zwischen dem urbanen und dem ländlichen Leben in Zusammenhang mit Ihrer Arbeit? Reagiert

das Publikum vom Land anders auf Ihre Werke als das Publikum aus der Stadt? Wir sprechen

ja inzwischen schon lange vom globalen Dorf, aber das war natürlich in Ihren

Anfangsjahren anders.

VE: Klarerweise reagiert das urbane Publikum anders als das ländliche Publikum,

weil es zum Teil schon dazu erzogen wurde, Bilder zu verifizieren, Bilder aufzunehmen

und sie auch anderen Bildern und bestimmten Strömungen zuzuordnen. Die Werbung zum

Beispiel fördert diese Fähigkeiten sehr. Das ländliche Publikum sieht ganz andere

Momente in der Kunst. Da stehen eher die Materialien, der Aufbau, das Sinnliche im

Zentrum. Das „Haptische fürs Auge“, glaube ich, sieht das ländliche Publikum viel mehr,

weil es viel mehr erweiterten Seheindrücken ausgesetzt ist. Das ländliche Publikum

erlebt und sieht die Natur stärker als das städtische, das ja viel weniger Bezug zum

natürlichen Ablauf eines Tages oder einer Nacht hat, denn in der Stadt ist es immer mehr

oder minder hell.

LOK: Der Sehsinn spielt dieses Jahr auch in unserem Ausstellungstitel eine

zentrale Rolle: „VALIE EXPORT. Ins Auge stechen“. Ich glaube, dass die gmunden.photo –

heuer erstmals als Einzelausstellung geplant – die Gelegenheit bietet, Ihre Arbeiten in

einer noch nicht da gewesenen Form zu sehen. Wir sind hier im öffentlichen oder halb

öffentlichen Raum und viele Menschen werden Ihr künstlerisches Werk in Gmunden wohl zum

ersten Mal sehen. Insofern ist der „Raum“ hier ein anderer als in einem Museum oder

einer Galerie. Ich bemühe mich in meiner kuratorischen Arbeit seit vielen Jahren darum,

Gegenwartskunst „für alle“ zu zeigen und zu vermitteln. Dennoch bin ich wegen einer

Konstante in Ihrem Werk auch sehr gespannt auf die Reaktionen des Publikums: Ich spreche

von der Wut, der Rage, die vor allem Ihr frühes Werk auszeichnet. Sind Sie auch heute

noch eine wütende Künstlerin?

VE: Die Wut habe ich immer noch, denn die gesellschaftlichen Zustände haben sich

ja kaum verändert. Im Gegenteil, man muss sagen, sie entwickeln sich zurück, werden

restriktiver, unterdrückender. Das liegt einfach an der Weltpolitik – die ist

ausschlaggebend für diese Sachen. Das war früher nicht so stark, denn man hat von der

Weltpolitik noch nicht so viel gewusst oder sie war doch nicht so im Bewusstsein. In den

1960er-Jahren war vieles freier, oder in Osteuropa früher – ich hatte in Moskau

beispielsweise sehr schöne und innovative Ausstellungen; da ist nun über die Jahre eine

riesige Lücke entstanden. Wir lassen den Osten nicht an uns heran und der Osten lässt

uns nicht an sich heran. Natürlich ist die Wut, der Zorn, die Ablehnung immer noch

vorhanden, weil sich nur langsam etwas ändert und wir alle in der Angst leben, dass es

noch schlechter wird. Wahlen werden beeinflusst, die Stimme des Volkes wird manipuliert.

Diese Angst ist sehr berechtigt.

LOK: Damit sind wir mitten in einer Mediendiskussion, denn unsere Wahrnehmung der

politischen Gegebenheiten wird natürlich massiv beeinflusst, ja regelrecht produziert

von der Berichterstattung und den Möglichkeiten der Medien, die sich in den letzten

Jahrzehnten sprunghaft entwickelt haben. Ich möchte noch einmal zurückkommen auf Ihre

künstlerische Arbeit. Man kann heute fast froh sein, wenn es dokumentarisches

Fotomaterial gibt von Aktionen oder Performances, die Sie in den 1960er-Jahren gemacht

haben. Wie wäre das denn heute, wenn man eine Aktion wie das TAPP- UND TASTKINO

öffentlich zeigen würde? Wie würde das Publikum reagieren? Was würde da im öffentlichen

Raum passieren?

VE: Ich glaube, so eine Aktion oder Performance wie das TAPP- UND TASTKINO wäre

heute nicht mehr möglich. Es würde sofort die Polizei kommen und mich abführen, und ich

würde eine Strafe bekommen. Das wäre heute alles viel schärfer. Dazumal war so eine

Aktion neu und dadurch war das Ganze auch freier. Die Gesellschaft war noch neugierig

und erwartungsvoll. Sie hat sich noch gespürt. Sie war im Aufbruch, hatte Utopien. Der

war wichtig damals, der utopische Gedanke. Heute könnte ich mir nicht vorstellen, was

ich für einen utopischen Gedanken entwickeln sollte. Das ist ein großer Verlust, denn

die Utopie braucht die Stärke der Gesellschaft, der Gegenwart.

LOK: Wesentlich ist auch die Rolle der sozialen Medien. Mit den heutigen medialen

Möglichkeiten würden sich die Bilder von Aktionen und Performances, wie Sie sie seit

über 50 Jahren machen, rasend schnell verbreiten, sie wären einfach überall im Netz.

Heute haben wir, glaube ich, auch enorm mit einer Überreizung und einem Überfluss an

visuellem Material zu kämpfen – wir müssen uns jeden Tag durch diese Flut von Bildern

wühlen und das Wichtige und Gute vom Unwichtigen und Unguten unterscheiden. Wir alle

können heute auf alles eine Kamera halten und verfügen im Netz über unbegrenzte

Möglichkeiten der Kommunikation, was einerseits demokratisch und gut ist, andererseits

aber auch zu Manipulation und Überfluss in höchstem Maß führt.

VE: Ja, sicherlich. Sie sagen genau, wie es ist. Das Manipulative wird viel

stärker, aber es wird auch sichtbarer. In den 1960er- und 1970er-Jahren war es nicht so

stark zu erkennen. Wir haben eine Nachkriegszeit erlebt, und da war alles noch viel

zurückhaltender und im Geheimen. Das ist der große Unterschied.

LOK: Wenden wir uns zum Schluss der nahen Zukunft zu. Wir haben beim

Atelierbesuch kurz darüber gesprochen: Österreich hat ja Florentina Holzinger für die

nächste Biennale in Venedig nominiert. Was erwarten Sie sich heute von feministischer

Performancekunst?

VE: Ich würde mir wünschen, dass sie sich stark mit den politischen Zuständen

beschäftigt, auch mit den verdeckten politischen Zuständen, den Weltzuständen. Das

klingt jetzt ein bisschen naiv (lacht). Man müsste wieder viel mehr demonstrieren, das

heißt auf die Straße gehen und sagen: „So wollen wir das nicht“ oder „Das wollen wir“.

Dann muss man gehört werden – wir haben ein Demonstrationsrecht. Im öffentlichen Raum

werden zu wenige Forderungen durch Gruppendynamik gestellt.

LOK: Das kann ich gut nachvollziehen. Das kam ja auch in dem öffentlichen

Künstlerinnengespräch so gut heraus, das Sie im November 2024 mit der

Pussy-Riot-Künstlerin Nadya Tolokonnikova im Wiener Museumsquartier geführt haben.

Tolokonnikova ist eine politische Aktivistin und Künstlerin und riskiert mit ihrer

künstlerischen Arbeit seit Beginn ihrer Karriere Kopf und Kragen.

VE: Ganz genau. Ich wünsche mir einfach mehr solche Ansätze. Das hat nichts mit

dem Alter zu tun. Das könnten Künstler:innen aller Generationen sein, die sich fragen:

In welcher Gesellschaft leben wir? In welcher Gesellschaft wollen wir leben? Was ist die

Vergangenheit dieser Gesellschaft? Wie soll die Zukunft dieser Gesellschaft aussehen? Es

ist eine Lebenshaltung. Wir haben nichts anderes als dieses Leben und das Leben muss

gestaltet werden.

LOK: Das war jetzt ein gutes Schlusswort für unser Gespräch. Mir war es eine

Ehre, dass ich Ihnen ein paar Fragen stellen durfte. Wir freuen uns sehr auf die

gmunden.photo 2025, die am 28. Juni eröffnet wird. Bis bald also in Gmunden.

VE: Sehr gerne.

Das Gespräch zwischen VALIE EXPORT und Lisa Ortner-Kreil fand am 8. Mai 2025 statt.

Lisa Ortner-Kreil (LOK):

Dear VALIE EXPORT, thank you so much for the opportunity to do an interview with you.

Let’s start with Gmunden. It’s an open-air exhibition, and the grounds of the public

town garden above the lake, formerly the municipal plant nursery, are situated amid a

very scenic landscape. Over the past years, working with various artists, I often

thought to myself that the wildness of the garden does have a very special kind of

attraction. So I would like to start by asking you whether you have a personal

relationship with Gmunden.

VALIE EXPORT (VE):

Oh yes, in the sense that I keep coming back to the Salzkammergut, to Bad Ischl and

Strobl, to visit with my sister. I usually go by car, and Gmunden is just the town where

you take a stop and have a cup of coffee and go for a walk or a snack. For me, Gmunden

is a beautiful place—a place that has a history, to be sure, like the whole

Salzkammergut, and a very tragic and sad history as well. Still, there is a certain

sense of optimism there. This is surely due to the lake. You can walk along the

esplanade and feel the calm of the lake or—when it’s windy—a somewhat rougher side of

it. You can also take a walk in Gmunden when it’s raining and stormy, with the houses

offering some shelter because it’s all so close and narrow, but the main square is

completely open. And there, you’re not just physically exposed to these forces of

nature; they also affect your vision. I always feel as if these forces can invade my

body and my perception.

LOK: It’s no coincidence that Gmunden and the Salzkammergut have always attracted

artists, and in recent years have significantly developed as a cultural venue thanks to

the festival Salzkammergut Festwochen and gmunden.photo. What I find interesting is that

physical perception you mentioned—what a place does to the body. The body, perception,

and language have been three pillars of your art work since the 1960s. In preparing

gmunden.photo, I’ve noticed that, on the one hand, your work has that well-known

toughness, sometimes violence, to it, and on the other, it moves in a lyrical field of

tension, being very language-oriented and poetic. So it’s at once tough and tender. How

has your view of your own work changed over time? After all, you’re celebrating your

eighty-fifth birthday this year.

VE: (Laughs.) Yes, that’s true. How to view one’s own works, that is a question

that’s hard to answer, because the works were created at one time, and I had my

intention then, my view, my will to express myself. That will to expression and

representation is something I still have. When I look at the works, it is there. I can

partly remember why, and from which roots, they came to be, that doesn’t change. But the

view of them changes, of course, if only because of changes in society. Because I ask

myself: What did I pick up on from society at the time, from the governing society, from

political, from cultural society? Did I pick up on the right things? It is a question

that I still confront myself with today. Not on a daily basis and not intensively, of

course, but mostly when I look at the works. My works are my life companions, they have

kept me company throughout my entire life as an artist. Looking at them, I also see, of

course, how my own life has changed. And how the connotations of my works are changing

and adapting. That really is the beauty of works of art—that you can perceive,

interpret, and take them in not only at one moment, in one period of time, but that they

also keep changing; by viewing them in the moment, you see the past, the future and,

above all, the present.

LOK: This change over time, of course, also has to do with social changes that

affect the perception of the works. On the other hand, I find the continuing topicality

of your work downright alarming. You started implementing your radical ideas, especially

on the role of women in society, in 1968. The issues from back then are still relevant

today, which says a lot about the state of our society and a feminism that, while

developing further, is also threatened by setbacks, and in the present political

circumstances does not see continuous forward development.

VE: Yes, that’s right. Politics keeps backsliding time and again, and that’s why

the works still have significance today. You can see that very well in feminism. Some

things have surely changed due to the feminist idea, feminist power. But many things are

still exactly as they were twenty or thirty years ago, because society takes a lot of

time to accept things and to change, and because it is dependent on global political

events. We don’t live in isolation, and art doesn’t live in isolation either. Art has

always been an expression of culture. You just have to go some time back in cultural

history. It has also had a lot to do with religion—which has imposed repressive rules on

society. It is something that art has also been dealing with.

LOK: As there is this strong connection with Upper Austria in your

biography—which is where you were born—and there also is the VALIE EXPORT Center in Linz

and now gmunden.photo, I would like to ask you: How do you see the difference between

urban and rural life in the context of your work? Do rural audiences respond differently

to your works than urban ones? We’ve been talking about the global village for quite

some time now, but that was of course a different story in your early years.

VE: Obviously, urban audiences react differently from rural ones, because they

have grown up being trained to verify images, to absorb images and also to categorize

them with other images and certain currents. Advertising, for example, very much helps

bringing out these skills. Rural audiences see completely different things in art. They

center more on materials, structure, the sensual aspect. The “haptic for the eye,” I

believe, is what rural audiences take in much more, because they are more exposed to

expanded visual impressions. A rural public experiences and sees nature more intensely

than an urban one, which can relate far less to the natural course of day or night,

because the city is always well-lit, more or less.

LOK: The sense of vision also plays a central role in our exhibition title this

year: “VALIE EXPORT: Hitting the Eye.” I think that gmunden.photo—planned for the first

time as a solo exhibition this year—provides an opportunity to see your work in an

unprecedented setting. We are in a public or semipublic space here, and many people will

probably be seeing your work for the first time ever in Gmunden. In this respect, the

“space” here is different from a museum or gallery. In my work as a curator, I have been

trying for many years to show, and convey, contemporary art “for everyone.” And yet, I

am very curious myself to see the reactions of the public because of one constant in

your work: I am speaking of the anger, the rage that particularly characterizes your

early work. Are you still an angry artist today?

VE: I still have that anger in me, because the social situation has in fact

hardly changed at all. On the contrary, you have to say it’s retrogressing, becoming

more restrictive, more oppressive. That simply has to do with global politics—it is what

shapes these matters. It wasn’t that strong in the past, because people didn’t know so

much about world politics or weren’t really much aware of it. In the 1960s, things were

much freer, or in Eastern Europe, back in the day—I had very beautiful and innovative

exhibitions in Moscow, for example; there has now been a huge gap there for years. We

don’t let the East get close to us, and the East doesn’t let us get close to them. Of

course, the anger, the rage, the rejection are still there because things are only

changing slowly, and we all live in the fear that things might get even worse. Elections

are being influenced; the voice of the people is being manipulated. This fear is very

much justified.

LOK: Which brings us right to a discussion about the media, since our perception

of political circumstances is of course massively influenced, and actually produced, by

media coverage and the possibilities of the media, which have developed by leaps and

bounds over the past few decades. I would still like to come back once more to your

artistic work. Today, we must almost be glad if there is documentary photo material of

art actions or performances that you did in the 1960s. What would it be like for an

action like the TAP AND TOUCH CINEMA to be shown in public today? How would the audience

react? What would be happening in the public space?

VE: I think an art action or performance like the TAP AND TOUCH CINEMA would not

be possible any longer today. Police would come and arrest me on the spot, and I would

be fined. It would all be a lot harsher today. Back then, this kind of action was

something new, and therefore everything was freer. Society was still curious and full of

expectation. It could still feel itself. It was on the move, had utopias. That was

important at the time, the utopian idea. Today, I couldn’t even imagine what kind of

utopian idea I should be developing. That is a great loss, because utopia needs the

strength of society, of the present.

LOK: Also essential here is the role of social media. With today’s media reach,

the images of actions and performances as you have been doing for over fifty years would

spread like wildfire, they would simply be everywhere on the net. Today, I think, we are

also struggling enormously with overstimulation and an overload of visual material—we

have to swim against a tide of images every single day, separating the important and

good from the unimportant and bad. Today, we can all hold up a camera to each and

everything and have unlimited opportunities to communicate online, which, on the one

hand, is democratic and good, but on the other also leads to manipulation and extreme

surfeit.

VE: Yes, for sure. You’re telling it exactly as it is. Manipulation is becoming

much stronger, but it’s also becoming more visible. It wasn’t that apparent in the 1960s

and ’70s. We lived through a postwar period when everything still was a lot more

reticent and secretive. That’s the big difference.

LOK: Finally, let’s turn to the near future. We talked briefly about this during

our studio visit: Austria has nominated Florentina Holzinger for the upcoming Venice

Biennale. What do you expect of feminist performance art today?

VE: I would want her to vigorously address the political situation, also the

covert politics, the state of the world. Well, that sounds a bit naive now (laughs). We

need to demonstrate a lot more again, take to the streets, that is, and say, “This is

not what we want” or “This is what we want.” We must make ourselves heard—we have a

right to demonstrate. Not enough public demands are made through group dynamics in the

public sphere.

LOK: I can very well understand that. And it came out so well in the public

artists’ talk you had with Pussy Riot artist Nadya Tolokonnikova in Vienna’s

Museumsquartier in November 2024. Tolokonnikova is a political activist and artist, and

she has been putting herself on the line in her artistic work ever since the start of

her career.

VE: Exactly. I would simply like to see more such approaches. This has nothing to

do with age. It could be artists of all generations asking themselves: What kind of

society do we live in? What kind of society do we want to live in? What is the past of

this society? What should the future of this society look like? It is an attitude to

life. We have nothing but this one life, and life must be shaped.

LOK: That was a good way to conclude our interview. It’s been an honor being able

to ask you some questions. We are very much looking forward to gmunden.photo 2025, which

opens on June 28. See you soon in Gmunden.

VE: With pleasure.

The conversation between VALIE EXPORT and Lisa Ortner-Kreil took place on May 8, 2025.

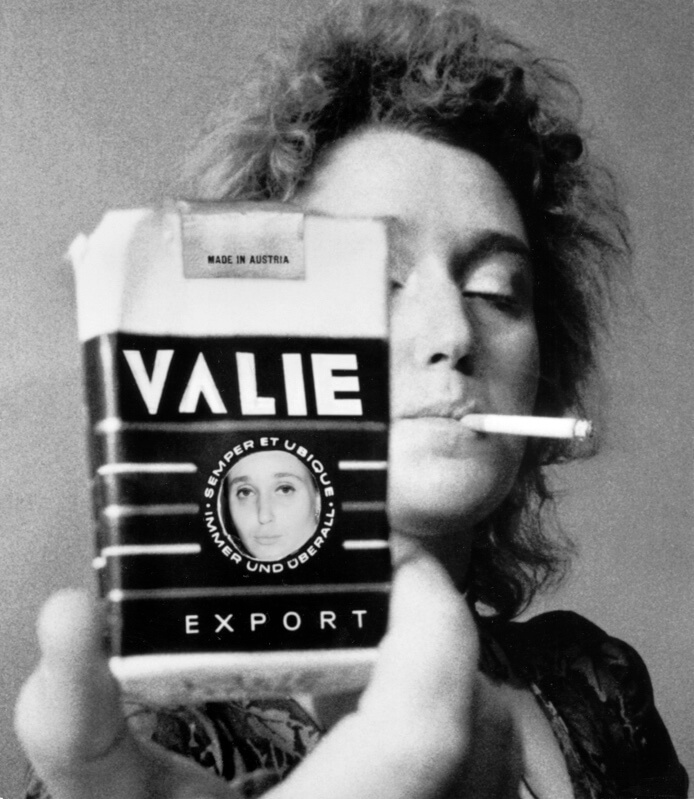

SMART EXPORT

1967 beschließt die Künstlerin Waltraud Höllinger geb. Lehner, sich einen neuen Namen zu

geben: VALIE EXPORT, in Großbuchstaben und urheberrechtlich geschützt. Damit befreit sie

sich nicht nur von den Namen ihres einstigen Ehemanns und ihres Vaters, sondern vollzieht

auch einen Akt der Selbstermächtigung. „VALIE EXPORT exportiert Ideen, das war der

Hintergrund“, sagt die Künstlerin in einem Interview. Auf dem fotografischen Porträt von

Gertraud Wolfschwenger aus dem Jahr 1970 posiert sie mit einer Packung der

österreichischen Zigarettenmarke Smart Export, die sie in die Kamera hält, während sie

selbst im Hintergrund steht, eine Zigarette lässig im Mundwinkel. Den ersten Teil des

Markennamens, „Smart“, hat sie durch „VALIE“ ersetzt; im Logo, einem Erdball mit dem Claim

„Semper et ubique – immer und überall“ darum herum, hat sie den Erdball mit einem

kreisrunden Selbstporträt überklebt. Mit dieser selbst ersonnenen Trademark entert sie die

Kunstszene und thematisiert Identität, Internationalität, Marktmechanismen und Kunst als

Ware, entzieht sich zugleich aber als Person. SMART EXPORT ist ein Schlüsselmoment in

ihrem künstlerischen Schaffen und eine frühe Ikone der feministischen Kunst.

In 1967, the artist Waltraud Höllinger, née Lehner, decided to give herself a new name:

VALIE EXPORT, in all capital letters and protected by copyright. In so doing, she not

only freed herself from her former husband’s and her father’s names but performed an act

of self-empowerment. “VALIE EXPORT exports ideas, that’s what was behind it,” the artist

said in an interview. In Gertraud Wolfschwenger’s photographic portrait of 1970, she

poses with a pack of Smart Export, an Austrian cigarette brand, which she holds up to

the camera, while she stays in the background, casually, with a cigarette in the corner

of her mouth. She replaced the first half of the brand name, “Smart,” with “VALIE”; in

the brand logo, a globe with the motto “Semper et ubique—always and everywhere” around

it, she overlaid the orb with a circular self-portrait. With this self-invented

trademark, she made her appearance on the art scene, addressing issues of identity,

internationality, market mechanisms, and art as a commodity while keeping a low profile

as a person. SMART EXPORT marks a key moment in her artistic work and is an early icon

of feminist art.

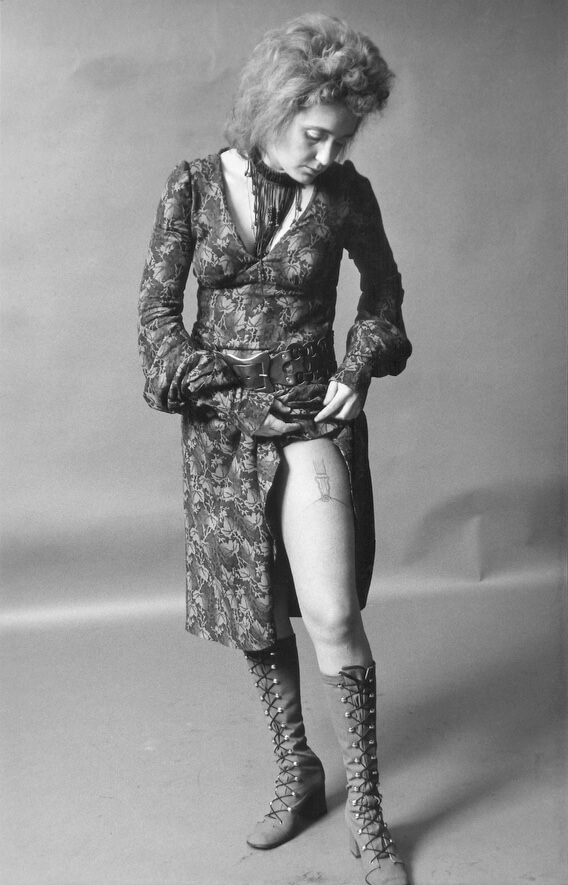

BODY SIGN ACTION

In dieser Performance, die 1970 im Studio Streckenbach in Frankfurt am Main stattfindet,

lässt sich die Künstlerin vom Tätowierer Horst Streckenbach ein Strumpfband in den Farben

Rot und Schwarz auf den Oberschenkel tätowieren. Radikal und schmerzhaft wird das

Strumpfband, das für die unterworfene und unterdrückte weibliche Sexualität steht, in den

Körper eingeschrieben, geht buchstäblich unter die Haut. Während die Detailaufnahme der

Tätowierung von der Künstlerin selbst stammt – der Körper ist hier nur als Fragment zu

sehen, die Künstlerin wird damit zu einer Stellvertreterin aller Frauen –, zeigt sich

VALIE EXPORT in Gertraud Wolfschwengers Ganzkörperporträt stehend, mit entblößtem

Oberschenkel. Tätowierung wird hier nicht als Körperschmuck verstanden, sondern als

geplanter und gesteuerter Akt der Einschreibung in den weiblichen Körper, selbst- und

fremdbestimmt gleichermaßen.

In this performance, which took place in 1970 at Studio Streckenbach in Frankfurt am

Main, the artist had a red and black garter tattooed on her thigh by tattoo artist Horst

Streckenbach. Radically and painfully, the garter, which stands for subjugated and

repressed female sexuality, is inscribed on the body, literally getting under the skin.

While the close-up of the tattoo was taken by the artist herself—with the body visible

here only as a fragment, making the artist a representative of all women—VALIE EXPORT is

shown standing in Gertraud Wolfschwenger’s full-body portrait, exposing her thigh. The

tattoo is not understood as a body ornament here but as a planned and controlled act of

inscription on the female body, equally self- and foreign-determined.

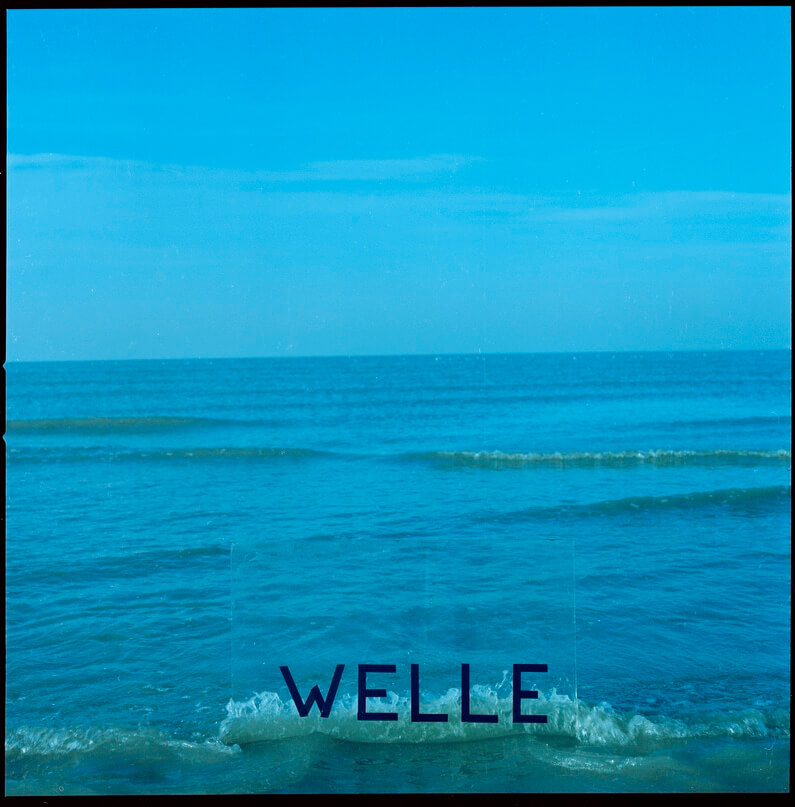

WELLE

Die Fotomontage WELLE aus dem Jahr 1972 setzt sich mit dem doppelten Charakter des

sprachlichen Zeichens auseinander: Der Schweizer Ferdinand de Saussure, Begründer der

modernen Sprachwissenschaft, unterschied schon vor über 100 Jahren zwischen der äußeren

Erscheinung eines Zeichens oder eines Wortes, also dem Lautbild oder der Buchstabenfolge,

und seiner Bedeutung. Das Foto zeigt eine Glasscheibe, auf der das Wort „WELLE“ in

Großbuchstaben aufgeklebt ist. Selbst fast unsichtbar, steht sie aufrecht im Wasser und

macht durch ihren Widerstand die Welle stärker sichtbar, die von hinten gegen sie schlägt.

Später dem Genre der „konzeptuellen Fotografie“ zugeordnet, demonstriert das Werk, das die

Künstlerin auf einem Abzug auch als „FOTO/POEM“ bezeichnet hat, ihre Fähigkeit, auf

alltägliche Gegebenheiten aufmerksam zu machen, die gemeinhin übersehen werden. Zugleich

kann es als Sinnbild für Widerstand verstanden werden. Die Glasplatte stört das ruhige

Auslaufen der Wellen am Ufer und benennt nicht nur ein Alltagsphänomen, sondern führt es

auch vor.

WAVE

The photomontage WAVE of 1972 deals with the dual character of the linguistic sign: more than one hundred years ago, the Swiss Ferdinand de Saussure, founder of modern linguistics, distinguished between the outward appearance of a sign or a word, that is, the sound pattern or sequence of letters, and its meaning. The photo shows a glass pane with the word “WELLE” (wave) written on it in adhesive capital letters. Almost invisible itself, it stands upright in the water and, posing a resistant obstacle, makes the wave running up against it from behind more visible. Categorized later in the genre of “conceptual photography,” the work, which the artist herself also labeled “FOTO/POEM” on one print, demonstrates her ability to draw attention to everyday realities that are commonly overlooked. At the same time, it can be understood as an emblem of resistance. The glass pane stands in the way of the calm ebbing of the waves on the shore and thus not only names an everyday phenomenon but also demonstrates it.

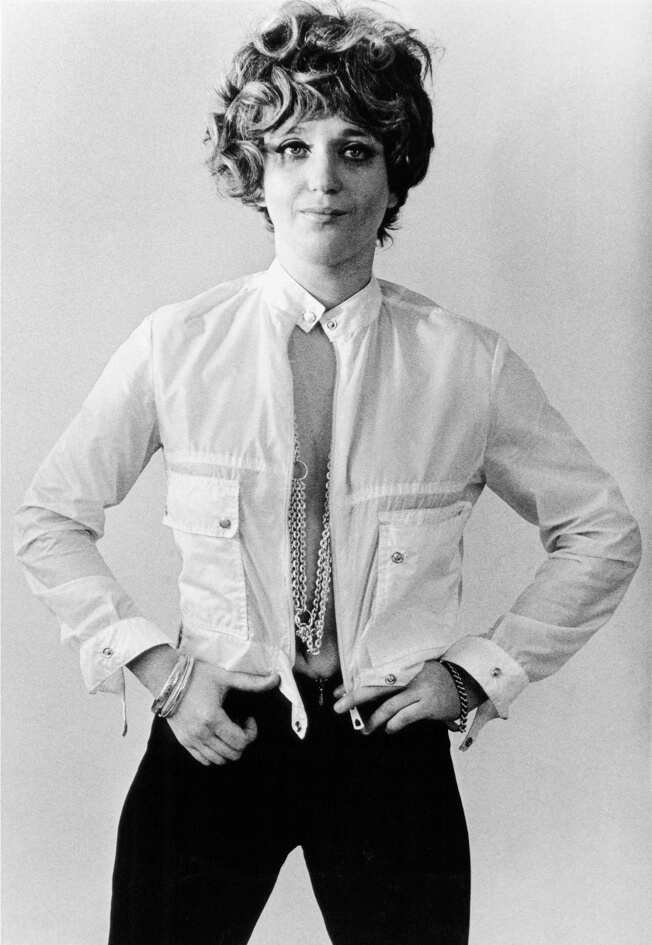

IDENTITÄTSTRANSFER

Die Arbeit ist eine fotografische Serie, in der sich die Künstlerin mit Geschlechterrollen

und der Konstruktion von Identität beschäftigt. VALIE EXPORT inszeniert sich selbst in

androgyner Erscheinung, trägt Perücke und eine Utility-Jacke, die einmal offen und einmal

geschlossen ist, sowie Halskette und Armreifen. Die Hände demonstrativ in die Hüften

gestemmt, wirkt sie im Bild mit der geschlossenen Jacke selbstbewusst und beherrscht,

während die Handhaltung auf dem Bild mit der offenen Jacke eher schützend, fast schüchtern

scheint. Was ist hier männlich? Was weiblich? Bereits früh hinterfragt VALIE EXPORT

traditionelle Zuschreibungen von Weiblichkeit und Männlichkeit – oder ganz allgemein

Systeme, die nur ein Entweder-oder kennen – und thematisiert eine vielschichtige, hybride

Identität. „Ich entschied mich, dass ich keine Identität habe bzw. eine Non-Identität“, so

die Künstlerin in einem Interview.

IDENTITY TRANSFER

The work is a photographic series in which the artist deals with gender roles and identity construction. VALIE EXPORT stages herself in an androgynous appearance, wearing a wig and a utility jacket, once open and once zippered, as well as a necklace and bracelet. With her hands assertively on her hips, she appears confident and self-possessed in the picture with the closed jacket, while, with the jacket open, the way she holds her hands seems rather protective, almost shy. What is masculine here? What is feminine? Early on, VALIE EXPORT started calling into question traditional assignments of femininity and masculinity—or, more generally, systems that only know an either-or—speaking to a multiform, hybrid identity instead. “I decided that I have no identity, or a nonidentity,” the artist said in an interview.

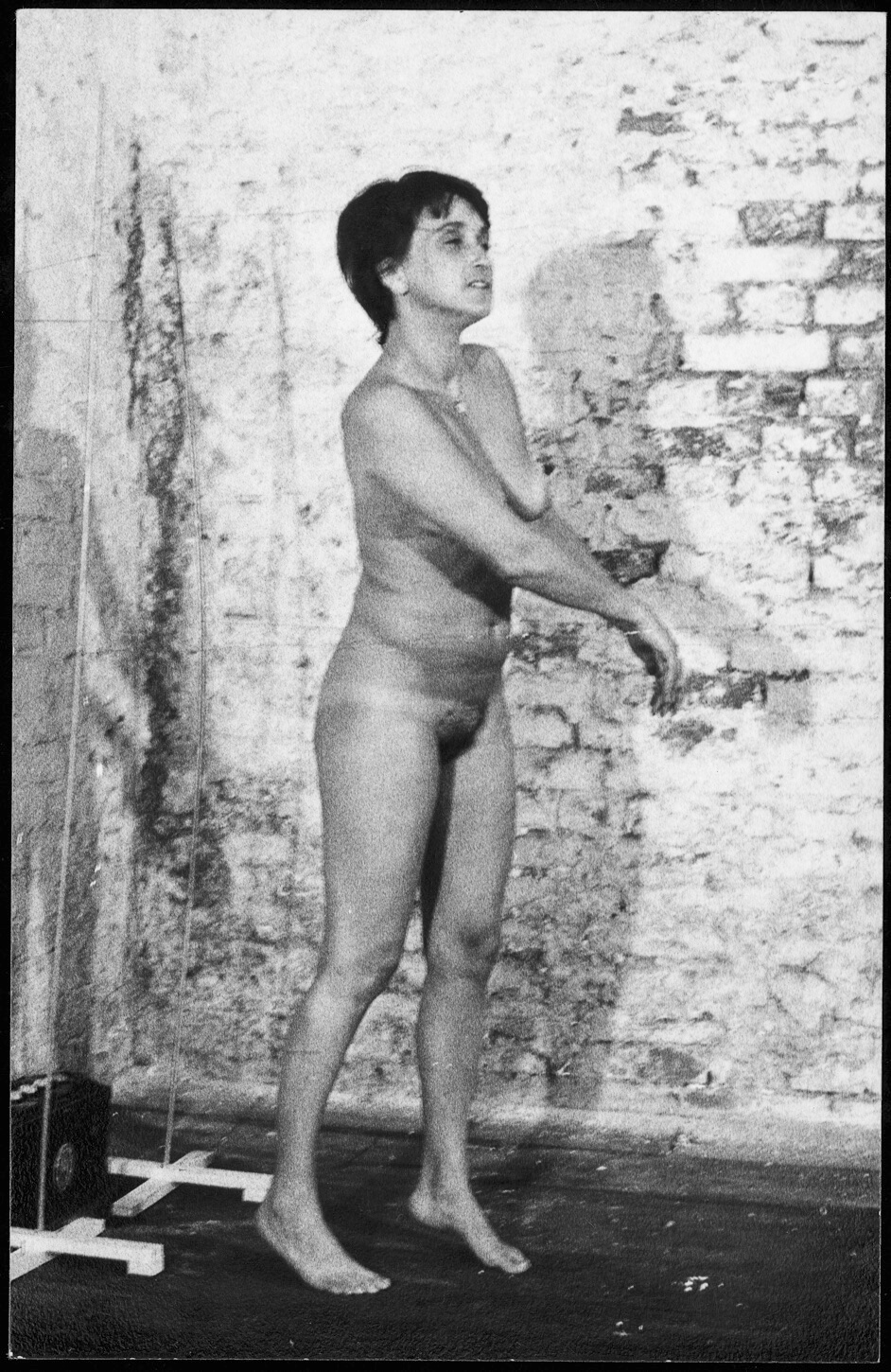

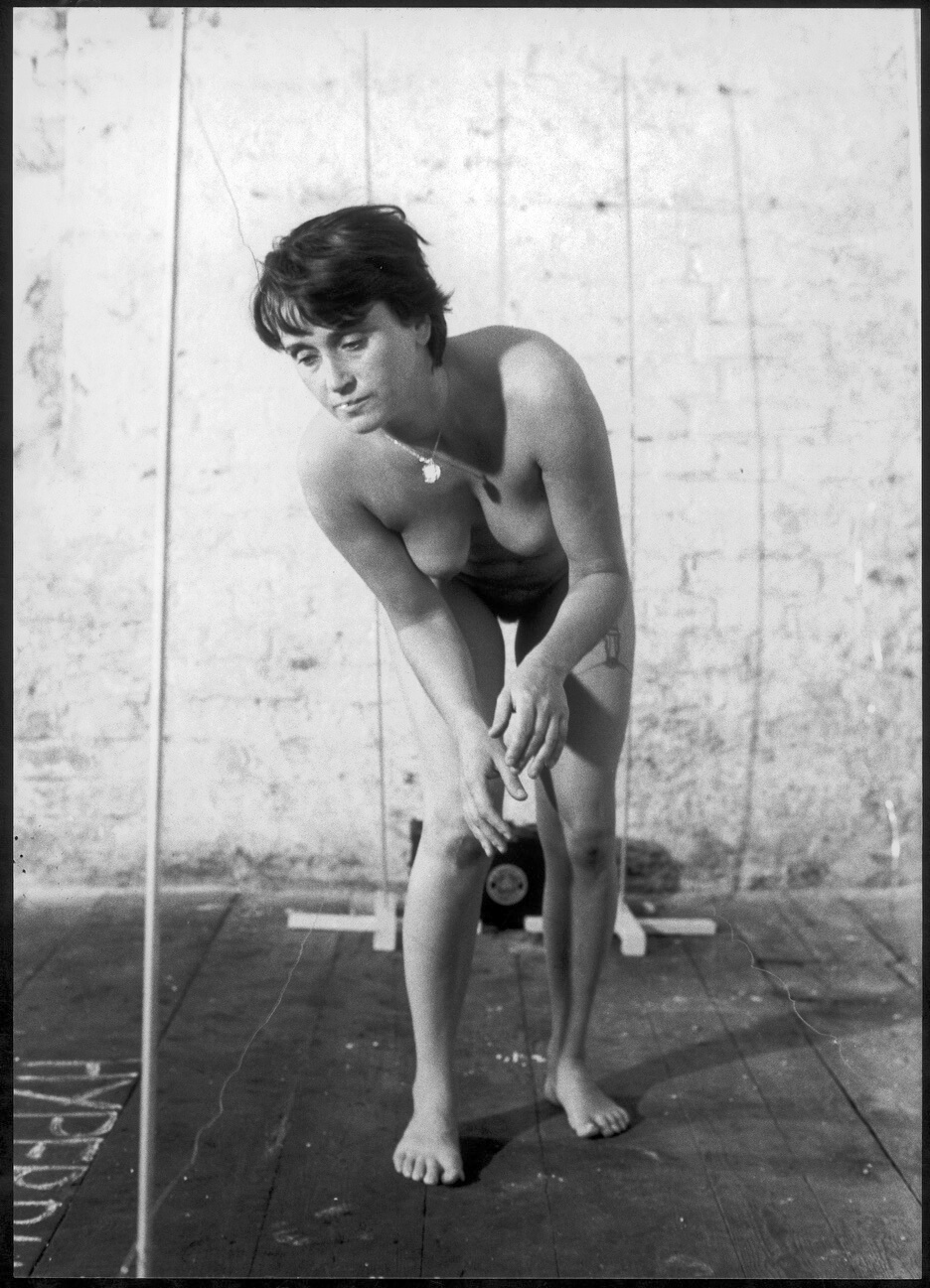

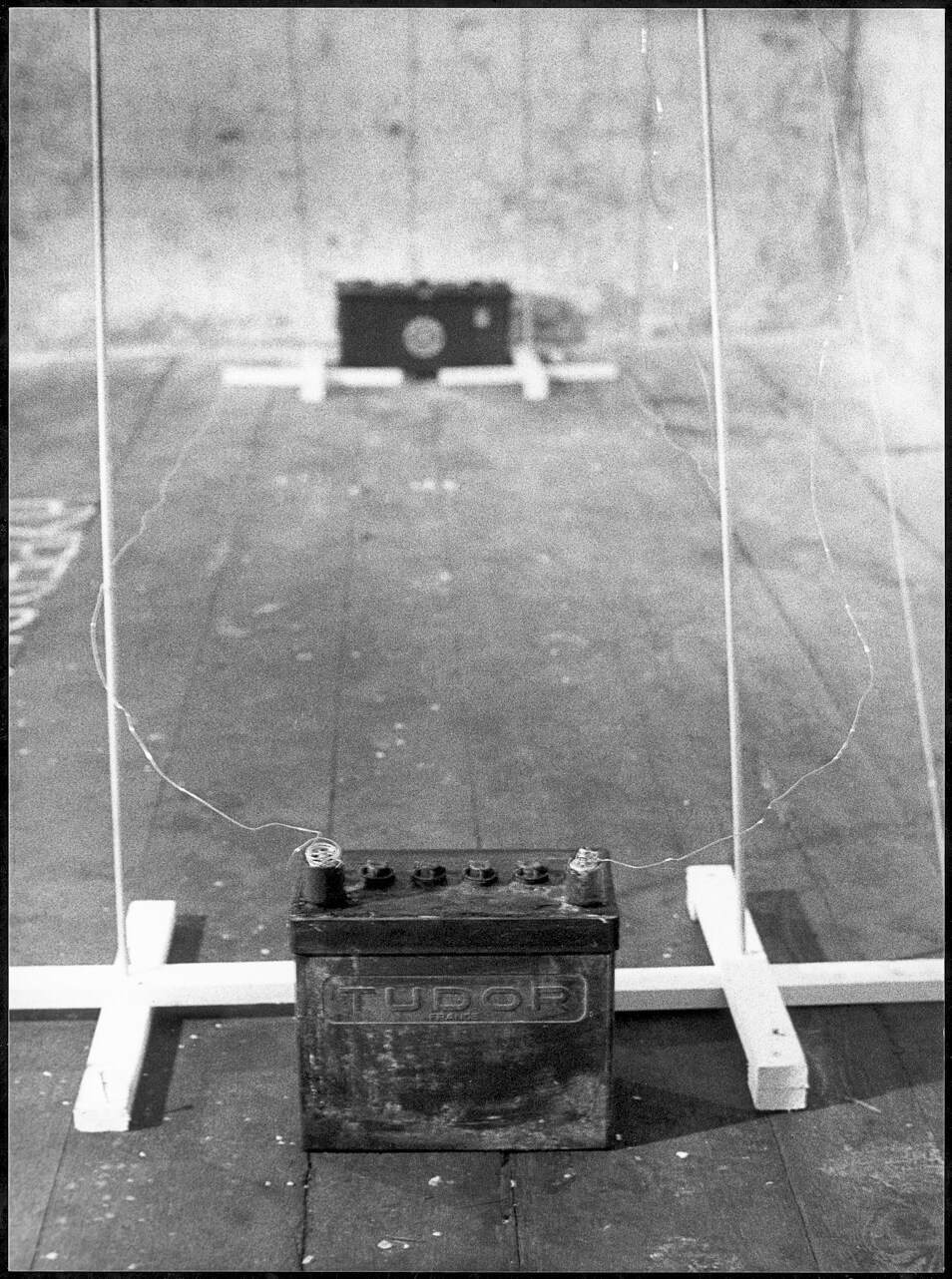

HYPERBULIE

HYPERBULIE ist eine Performance, mit der die Künstlerin sowohl physisch als auch psychisch

an die Grenzen ihres Körpers geht. Nackt bewegt sie sich durch einen schmalen Korridor,

der von elektrisch geladenen Drähten gebildet wird. Jeder Kontakt mit den Drähten versetzt

ihr einen Stromschlag, ein Sinnbild für den Verstoß gegen gesellschaftliche Normen.

Zunächst noch aufrecht stehend, wird die Künstlerin bald in die Knie gezwungen:

Gesellschaftliche Gegebenheiten, veranschaulicht durch den Korridor aus elektrischen

Drähten, machen das Individuum gefügig, disziplinieren es trotz aller Willensstärke. Die

Performance endet mit einem Akt der Befreiung – die Künstlerin kämpft sich aus dem

Korridor heraus. Die physische und psychische Belastung, die gesellschaftliche Normen

darstellen, und der Einsatz, der notwendig ist, um sich davon zu befreien, werden

pointiert und erbarmungslos dargestellt.

HYPERBULIE is a performance in which the artist pushes the limits of her own body both

physically and psychologically. Naked, she moves along through a narrow corridor made up

of electrically charged wires. Each contact with the wires gives her an electric shock,

symbolizing a violation of social norms. Standing tall at first, the artist is soon

forced to her knees: social conditions, epitomized by the corridor of electric wires,

make the individual submissive, disciplining them no matter how strong their will is.

The performance ends with an act of liberation—the artist fighting her way out of the

corridor. The physical and psychological burden that social norms represent and the

effort it takes to free oneself from them are represented in a poignant and unsparing

manner.

BODY POLITICS

BODY POLITICS ist ein circa dreiminütiger Schwarz-Weiß-Videofilm, der in der

Schottenpassage in Wien aufgenommen wurde. Zu sehen sind zwei Rolltreppen, eine führt nach

oben, eine nach unten. Sie werden jeweils von einem Mann und einer Frau benutzt. Die

beiden sind mit einem Seil verbunden, das sie um den Leib gebunden haben. Kurze

Texteinblendungen am Anfang jeder Sequenz („gegeneinander“, „miteinander“, „einander“)

machen die Dynamiken zwischen den Körpern im Raum und zwischen den Geschlechtern greifbar.

Die Künstlerin hat in Interviews betont, dass die Rolltreppen für Kommunikations- und

Repräsentationssysteme stehen, die kaum zu umgehen sind. Erst in der allerletzten Sequenz

benutzen der Mann und die Frau dieselbe Rolltreppe und fahren gemeinsam nach oben.

BODY POLITICS is an approximately three-minute black-and-white video film shot in the

Schottenpassage, an underground tram and subway passage in downtown Vienna. It shows two

escalators, one going up and one going down. They are each used by a man and a woman.

The two are connected by a rope tied around their bodies. Short text inserts at the

beginning of each sequence (“gegeneinander,” against each other; “miteinander,” with

each other; “einander,” each other) make the dynamics between the bodies in space and

between the genders palpable. In interviews, the artist emphasized that the escalators

stand for systems of communication and representation that can hardly be circumvented.

It is only in the very last sequence that the man and the woman use the same escalator

and move upward together.

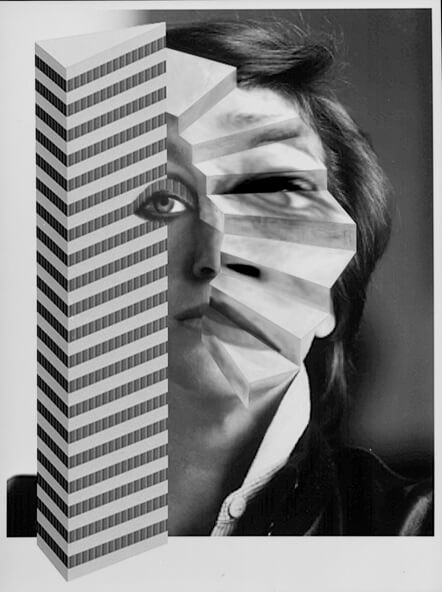

SELBSTPORTRÄT MIT STIEGE UND HOCHHAUS

SELBSTPORTRÄT MIT ZWEI HOCHHÄUSERN

Die zwei Arbeiten sind Beispiele für frühe digitale Fotografien. VALIE EXPORT kombiniert

in beiden Porträts ihr Konterfei mit architektonischen, städtischen Elementen. Die Treppe

steht für Bewegung, Übergang und vielleicht auch Hierarchie, während das Hochhaus auf das

soziale Gefüge der Stadt verweist. Mikrostruktur (das frontale Selbstporträt) und

Makrostruktur (die städtischen Elemente) finden zusammen. Die Themen sind Körper, Raum und

Machtmechanismen, auch der Akt des Sehens selbst. Auf beiden Porträts ist es die

Augenpartie, die den Übergang vom einen ins andere Motiv bildet: Ein Auge ragt in die

Front des Hochhauses oder wird auf der sich wie eine Ziehharmonika ausfächernden Treppe

überdimensional groß.

SELF-PORTRAIT WITH STAIRS AND HIGH-RISE

SELF-PORTRAIT WITH TWO HIGH-RISES

These two works are examples of early digital photographs. In both portraits, VALIE EXPORT combines a picture of her face with architectural, urban elements. The staircase stands for movement, transition, and maybe also hierarchy, while the high-rise building refers to the social structure of the city. Microstructure (the frontal self-portrait) and macrostructure (the urban elements) come together. Thematically, the works are about the body, space, and mechanisms of power as well as the act of seeing itself. In both portraits, it is the eye area that marks the overlap of one motif with the other: an eye looks out of the front of the high-rise building or is enlarged out of all proportion by the stairs that fan out like an accordion.

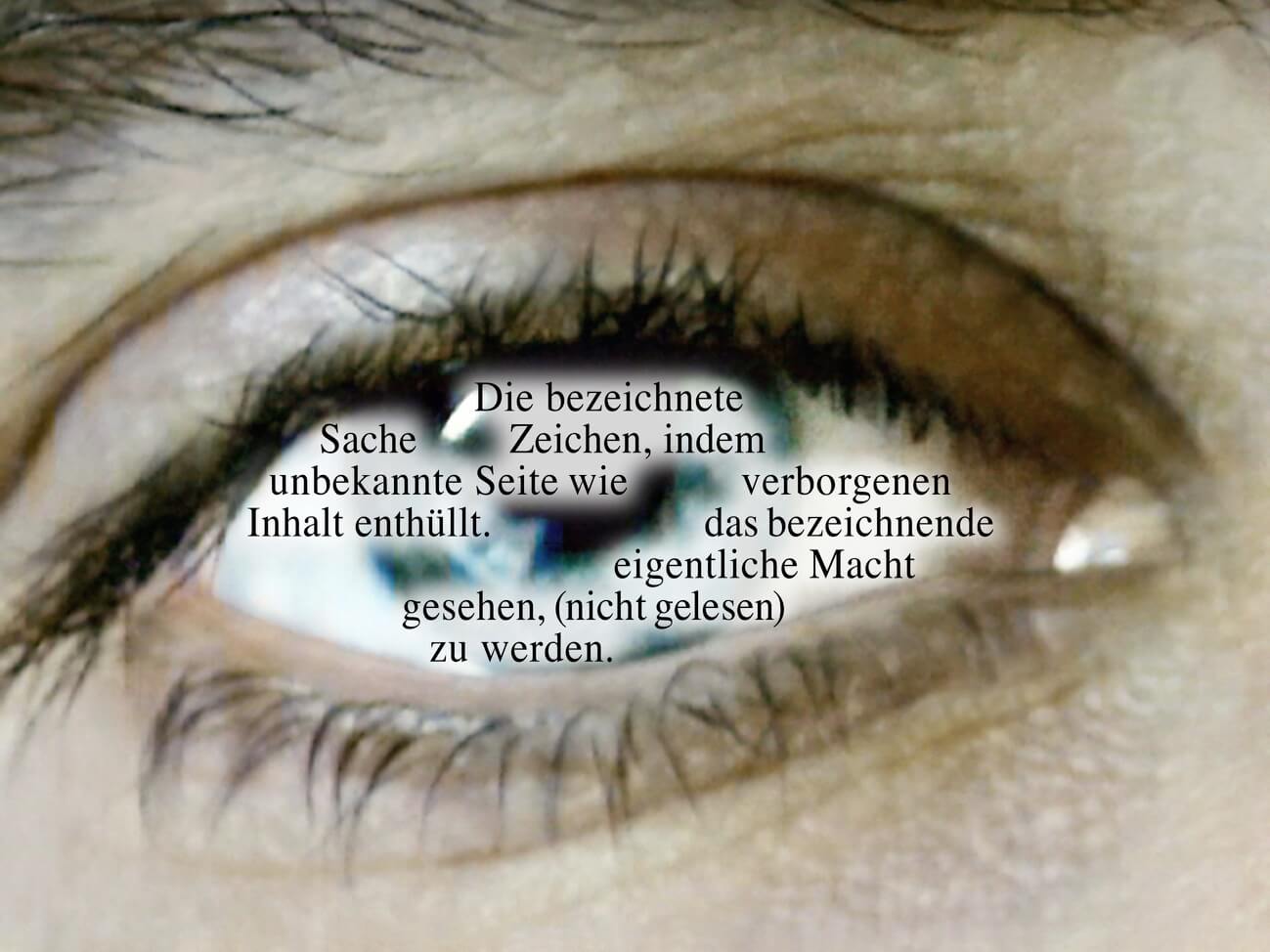

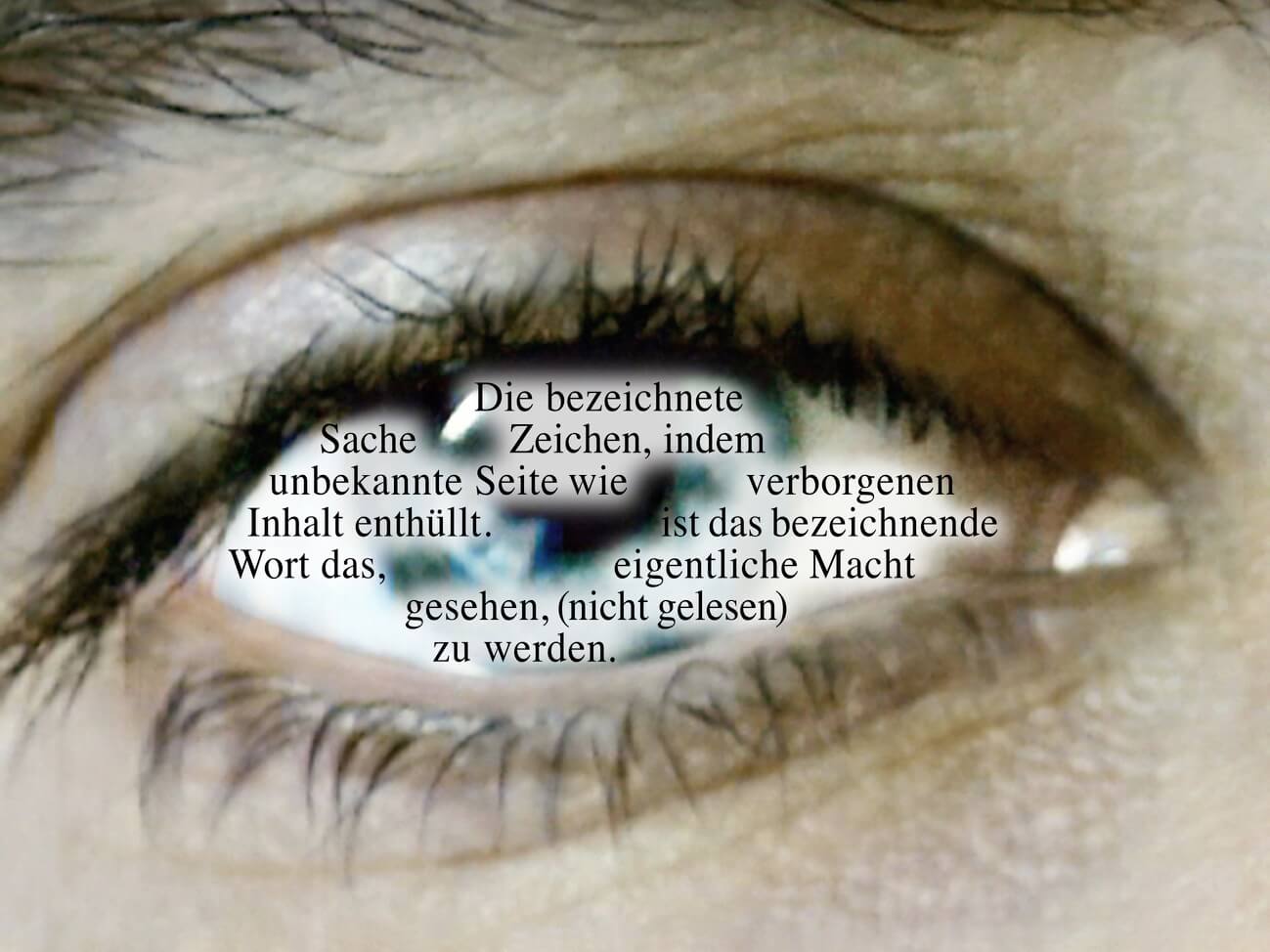

DER BLICK DES BLICKES

Diese Arbeit, deren Konzept auf 1992 zurückgeht, ist als mehrteilige fotografische Serie

angelegt: Großaufnahmen eines Auges werden mit Text- und Satzfragmenten kombiniert, in

denen es um Sehmechanismen, Wahrnehmung und mediale Repräsentation geht. VALIE EXPORT

interessiert der Weg, den der menschliche Blick nimmt – das Prinzip des Eyetrackings, das

heute in der Medizin, der Psychologie, der Werbung, aber auch beim Gaming und in der

Virtual Reality zum Einsatz kommt. Außerdem geht es um die Fragen: Was ist Realität? Was

ist Abbildung? Was kann und will die Fotografie in diesem Zusammenhang leisten? Wie ist

das Verhältnis von Botschaft, Sender:in und Empfänger:in? In unserem digitalen Zeitalter

werden diese Fragestellungen immer komplexer.

THE GAZE’S GAZE

This work, the concept of which dates back to 1992, is designed as a multipart photographic series: close-ups of an eye are combined with fragments of text and sentences that are about mechanisms of vision, perception, and media representation. VALIE EXPORT is interested in the path that the human gaze pursues—the principle of eye tracking, which is routinely used today in medicine, psychology, and advertising, but also in gaming and virtual reality. The questions addressed also include: What is reality? What is representation? What can and will photography achieve in this context? What is the relationship between message, sender, and receiver? In our digital age, these questions are becoming increasingly more complex.

TAPP- UND TASTKINO

Diese Aktion führt VALIE EXPORT erstmals 1968 in Wien durch. Die Künstlerin trägt einen

Kasten um den Oberkörper, der wie ein Miniaturkinosaal gestaltet ist, mit einem kleinen

Vorhang zum Publikum hin. Sie lädt dazu ein, für zwölf Sekunden durch den Vorhang zu

greifen und ihre nackten Brüste zu berühren. Die Menschen tasten im Kasten herum, während

sie der Künstlerin in die Augen schauen. Ausgangspunkt ist die Idee des Expanded Cinema,

also eines erweiterten, experimentellen Kinos, das über die klassische Leinwandprojektion

hinausgeht und in den 1960er-Jahren aufgekommen ist. Der Körper wird zur Leinwand, der

Kasten ist der Kinosaal. Nicht nur der Sehsinn, sondern auch der Tastsinn wird zur

Erkundung des Werks eingesetzt. Peter Weibel, mit dem VALIE EXPORT in diesem Jahr auch für

die Aktion AUS DER MAPPE DER HUNDIGKEIT zusammenarbeitet, fordert Passant:innen mit einem

Megafon zum „Kinobesuch“ auf. In der Performance geht es um den Sehakt, den männlichen

Blick und die voyeuristische Natur des klassischen Kinos, in dem das Publikum im Dunkeln

sitzt und auf die Leinwand blickt. Die Künstlerin bezeichnet die Arbeit als „Hautfilm“ und

„ersten mobilen Frauenfilm“. Das Video des TAPP- UND TASTKINOS entsteht etwas später für

das österreichische Fernsehen.

TAP AND TOUCH CINEMA

VALIE EXPORT first performed this art action in Vienna in 1968. The artist wore a box mounted in front of her chest, designed like a miniature movie theater with a small curtain facing the audience. She invited people to reach through the curtain for twelve seconds and touch her naked breasts. People were fumbling around in the box while looking the artist in the eye. The starting point of this was the idea of “expanded cinema,” that is, a more immersive experimental cinema that goes beyond classic screen projection and emerged in the 1960s. The body becomes the screen, the box is the movie theater. Not only the visual but also the tactile sense is engaged to explore the work. Peter Weibel, with whom VALIE EXPORT had also collaborated for the action FROM THE PORTFOLIO OF DOGGISHNESS earlier that year, invited passers-by through a megaphone to come “visit the cinema.” The performance is about the act of seeing, the male gaze, and the voyeuristic nature of classic cinema, where the audience sits in the dark looking at the screen. The artist describes the work as a “skin film” and the “first mobile women’s film.” The video of the TAP AND TOUCH CINEMA was made a little later for Austrian television.

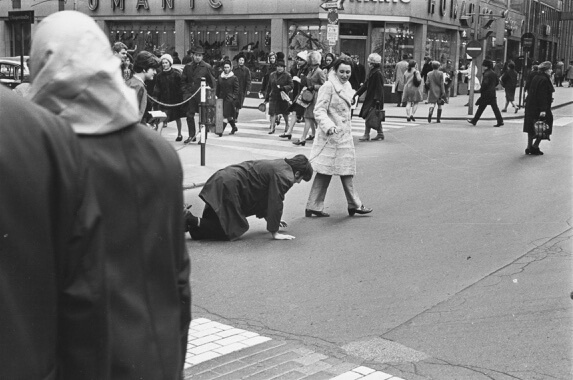

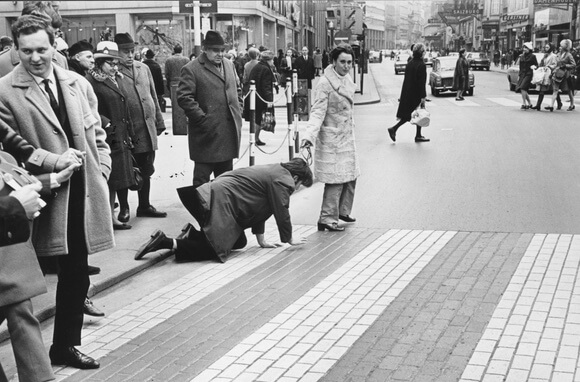

AUS DER MAPPE DER HUNDIGKEIT

Im Februar 1968 führt VALIE EXPORT ihren Künstlerkollegen und Partner Peter Weibel an

einer Hundeleine durch die Kärntner Straße in Wien. Weibel bewegt sich auf allen vieren,

EXPORT trägt bürgerliche Kleidung. Schon vorher ist das Paar so zu einer Eröffnung in der

Galerie nächst St. Stephan gegangen. Die Künstlerin berichtet später in vielen Interviews

über die erstaunten und belustigten Reaktionen des Publikums. Einerseits kehrt die

Performance das Machtverhältnis zwischen Mann und Frau um, das in den 1960er-Jahren noch

viel ungleicher war als heute: Die Frau wird zum aktiven Part und führt den sich

unterwerfenden, „hündischen“ Mann am Gängelband. Wichtig ist EXPORT und Weibel auch die

künstlerische Entscheidung, den Menschen zum Tier zu machen. Der öffentliche Raum und die

Reaktion des Publikums werden bewusst einbezogen. Die Künstlerin bezeichnet die Arbeit

später als „Fallstudie der Soziologie und des menschlichen Verhaltens“. Die Fotos stammen

von Josef Tandl.

FROM THE PORTFOLIO OF DOGGISHNESS

In February 1968, VALIE EXPORT led her fellow artist and partner Peter Weibel on a dog leash through Kärntner Strasse, Vienna’s most elegant shopping street. Weibel was moving along on his hands and knees with EXPORT walking beside him in a bourgeois furry coat. The couple had previously attended an opening event at the Galerie nächst St. Stephan like this. In many interviews, the artist later recounted the perplexed and amused reactions of the public. On the one hand, the performance reversed the power relation between man and woman, which was much more unequal in the 1960s than it is today: the woman takes the active part and keeps the submissive “doggish” man on a rein. Also significant for EXPORT and Weibel was their artistic decision to turn a human into an animal. The public space and the reaction of the audience were consciously involved in the action. The artist later described the work as a “case study of sociology and human behavior.” The photos are by Josef Tandl.

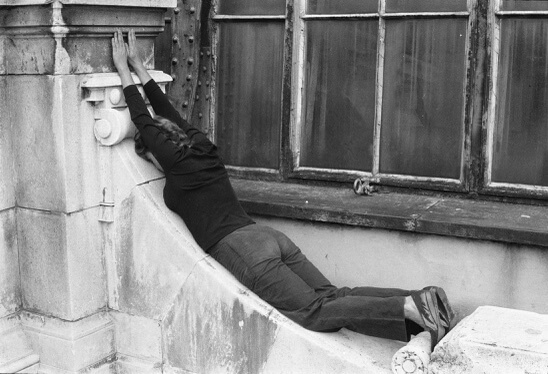

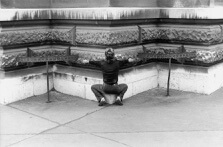

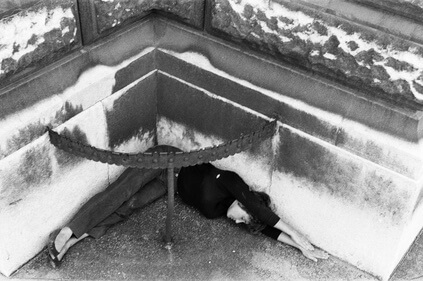

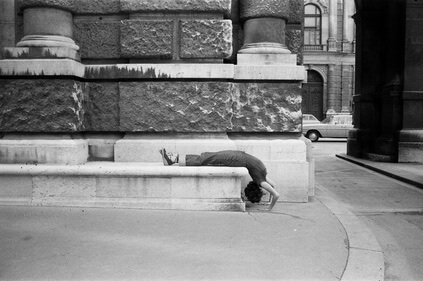

KÖRPERKONFIGURATIONEN

Die Serie der KÖRPERKONFIGURATIONEN entsteht über einen Zeitraum von zehn Jahren in

insgesamt vier Abschnitten. VALIE EXPORT untersucht darin die Rolle des weiblichen Körpers

im Kontext von Architektur und Stadtbild. Für die Künstlerin erfährt sich der Körper durch

seine Umgebung, sie spricht auch vom „Umgebungskörper“. Die Körperhaltungen, die sie

einnimmt, sind Ausdruck eines inneren Zustands und ahmen die Gegebenheiten des städtischen

Umfelds nach, konterkarieren sie aber auch. Die Künstlerin hockt „um die Ecke“ der

Nationalbibliothek in Wien, breitet die Arme zur Kreuzform aus, lässt im Liegen ihren Kopf

nach unten hängen oder biegt ihren Körper parallel zu einer Kurvenform. Titel wie

ANPASSUNG oder EINFÜGUNG machen deutlich, dass sie mit nichts anderem als ihrem Körper den

öffentlichen Raum vermisst, der immer auch ein Herrschafts- und Repräsentationsraum ist.

Mit ihren künstlerischen Interventionen untersucht sie diesen auf gesellschaftliche

Machtstrukturen hin.

BODY CONFIGURATIONS

The BODY CONFIGURATIONS series was created in four sections over a period of ten years. VALIE EXPORT examines the role of the female body in the context of architecture and the cityscape. For the artist, the body experiences itself through its environment; she also speaks of the “environed body.” The postures she adopts are an expression of an inner state, imitating, but also counteracting, the conditions of the urban environment. The artist squats “around the corner” from the National Library in Vienna, spreads her arms out into a cross shape, lets her head hang down while lying down, or bends her body parallel to a curved shape. Titles such as ANPASSUNG (Adjustment) or EINFÜGUNG (Insertion) make it clear that she uses nothing but her body to measure out public space, which always also is a space of domination and representation. With her artistic interventions, she examines that space for social power structures.

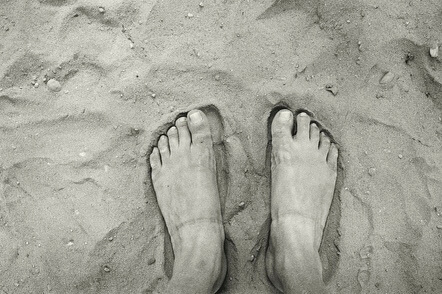

ONTOLOGISCHER SPRUNG

Bei dieser Arbeit handelt es sich um eine Bild-im-Bild-Konstruktion, die Performance und

konzeptuelle Fotografie verbindet. Für die eigentlich dreiteilige Serie fotografiert VALIE

EXPORT zuerst ihre Füße im Sand, von oben und in Schwarz-Weiß. Der zweite, in Gmunden

nicht ausgestellte Teil ist eine Farbfotografie, die wieder die Füße der Künstlerin zeigt

– diesmal aber stehen sie auf einem Abzug der ersten Fotografie, neben den Füßen aus der

ersten Aufnahme. Der dritte Teil treibt das Spiel noch weiter: Hier stehen die Füße auf

einem Abzug der zweiten Fotografie, und zwar genau auf den Füßen aus der ersten Aufnahme.

Die Fotografie liegt auf einem Teppich in einem Innenraum. Die Arbeit ONTOLOGISCHER SPRUNG

befragt die Fotografie selbst, ihren Status als Reproduktion: Was bedeutet „real“? Was ist

„nur“ ein Bild von Realität? Zu erkennen, was man auf den Aufnahmen sieht, ist wegen der

mehrfachen Kombination von Abbild und Wirklichkeit nicht einfach. Der Körper – VALIE

EXPORTs Lebensthema – wird hier fragmentiert und verdoppelt, durch die Fotografie ist er

gewissermaßen unendlich vervielfältigbar.

ONTOLOGICAL LEAP

This work is a picture-within-a-picture construction that combines performance and conceptual photography. For what is actually a three-part series, VALIE EXPORT first photographed her feet in the sand, from above and in black and white. The second picture, not on view in Gmunden, is a color photograph that again shows the artist’s feet—but this time they are seen standing on a print of the first photograph, right next to the feet from the first shot. The third part takes the game even further: here, the feet are standing on a print of the second photograph, exactly on top of the feet from the first shot. The photograph is laid out on a carpet in an indoor room. The work ONTOLOGICAL JUMP interrogates photography itself, its status as a reproduction: What does “real” mean? What is “just” an image of reality? Identifying what can be seen in the photos is not easy because of the multiple combination of image and reality. The body—VALIE EXPORT’s lifelong theme—is fragmented and doubled here, made infinitely reproducible, as it were, through photography.

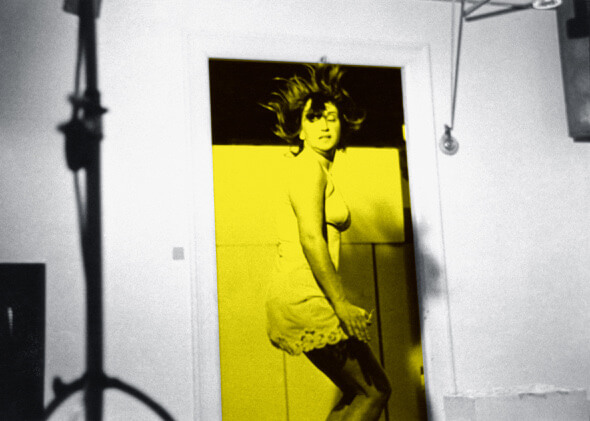

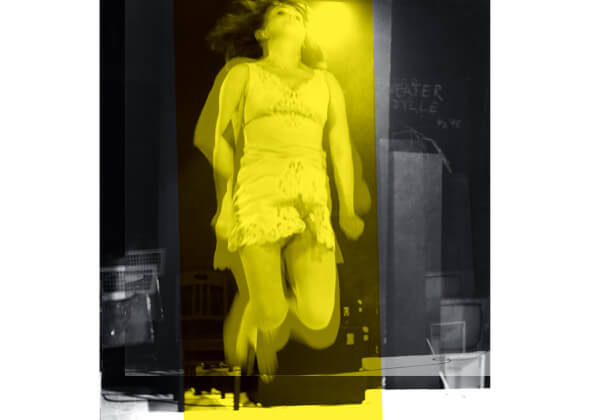

JUMP

Diese Arbeit wurde 2009 in zwei Editionen mit den Titeln JUMP 1 und JUMP 2 veröffentlicht

und bezieht sich auf eine Videoperformance oder „Bewegungsimagination“, wie es die

Künstlerin auch nennt, aus dem Jahr 1974. In mehreren Protokollen und Anleitungen

beschreibt VALIE EXPORT die Hintergründe der Arbeit und nennt unter anderem

„Körperbelastung, Körperspannung, Körperprobungen und Körpergrenzen“ als ihren Fokus.

„Bewegungsimaginationen sind körperliche Demonstrationen jener Passion des Menschen, den

extremsten Bedingungen so lange als möglich zu widerstehen. Bewegungsimaginationen sind

also Konkretionen der menschlichen Imagination, die gegen jede Art von Grenzen anläuft.“

Fotografisch festgehalten wird der Moment des Sprungs als Auflösung einer nicht mehr

ertragbaren Situation.

This work was published in 2009 in two editions entitled JUMP 1 and JUMP 2 and refers to

a video performance or “movement imagination,” as the artist also calls it, of 1974. In

several logs and instructions, VALIE EXPORT describes the background to the work,

naming, among other things, “body strain, body tension, body testing, and body limits”

as her focus. “Movement imaginations are bodily demonstrations of the human passion to

withstand the most extreme conditions for as long as possible. Movement imaginations

therefore are concretions of the human imagination running up against all kinds of

limits.” What is photographically captured is the moment of the jump as the resolution

of a no longer bearable situation.

I AM BEATEN

Diese Videoperformance aus dem Jahr 1973 ist eine Auseinandersetzung mit Gewalt,

Körperlichkeit und medialer Darstellung. VALIE EXPORT liegt rücklings am Boden. Man hört

eine Tonsequenz, in der eine Stimme „I am beaten“ sagt. VALIE EXPORT verdoppelt diese

Stimme, indem sie den Satz mitspricht. Veranschaulicht werden Niederlage und Unterwerfung

(durch die Körperposition), aber auch Widerstandsfähigkeit (durch das Mitsprechen im

wörtlichen Sinn, das auf ein Mitsprechen im übertragenen Sinn verweist).

This video performance of 1973 is an examination of violence, physicality, and media

representation. VALIE EXPORT is seen lying on her back on the floor. A soundtrack is

heard, with a voice saying “I am beaten.” VALIE EXPORT doubles this voice in that she

joins it in speaking the sentence. What this illustrates (through the body position) is

defeat and submission but also resilience (the literal act of speaking up connotes the

figurative meaning of the phrase).

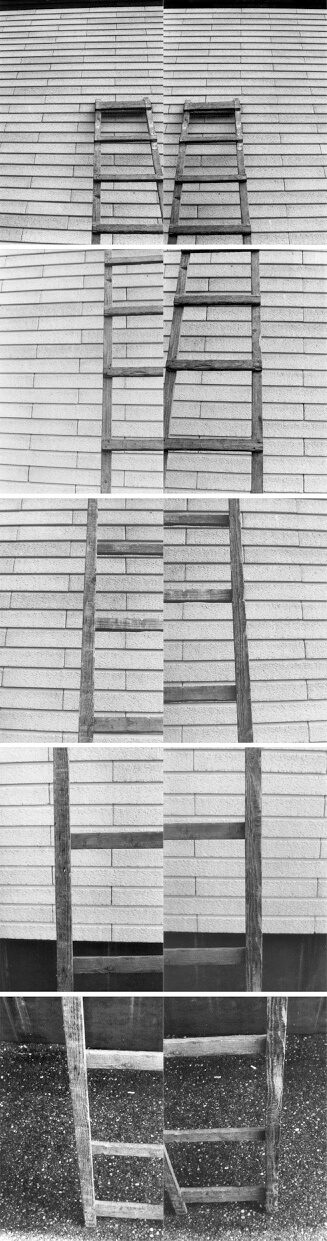

LEITER

Bei der Arbeit handelt es sich um eine konzeptuelle Fotocollage als Teil einer Serie, die

sich mit weiblicher Anatomie und weiblichen Körperbildern beschäftigt. Die Künstlerin hat

dafür Ausschnitte aus mehreren Fotos von Leitern zum Bild einer langen Leiter

zusammengefügt. Damit spielt sie einmal mehr auf gesellschaftliche Strukturen, Hierarchien

und Machtpositionen an: Wo steht ein Individuum auf der sozialen Leiter? Auf das unterste

Bild der Collage hat sie einen Satz geschrieben, der fast wie ein Liebesgedicht wirkt:

„MEINE AUGEN KLETTERN DIE LEITER DER LIEBE HINAUF UM DIE ZEIT AN DEINEM MUND ZU

TREFFEN.“

LADDER

This piece is a conceptual photo collage as part of a series dealing with female anatomy and female body images. The artist combined excerpts from several photos of ladders to create an image of a long ladder. In doing so, she once again alludes to social structures, hierarchies, and positions of power: Where does an individual stand on the social ladder? On the bottom image of the collage, she has written a sentence that almost reads like a love poem, “MY EYES CLIMB UP THE LADDER OF LOVE TO MEET TIME AT YOUR MOUTH.”

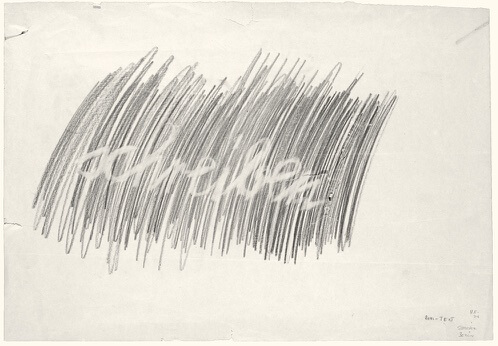

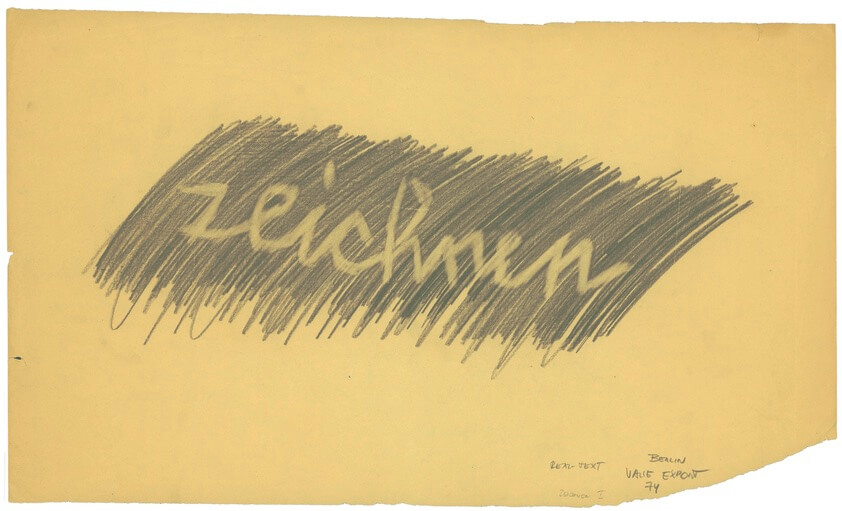

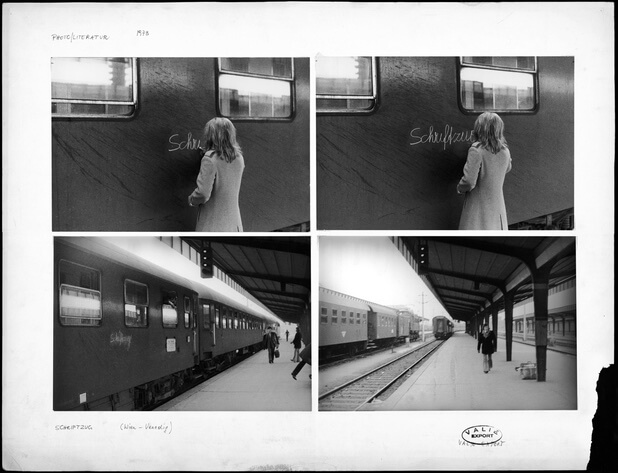

SCHREIBEN

ZEICHNEN

Schriftzug Wien - Venedig

Gedichte

Hauchtext: Liebesgedicht

SPRACHE ALS MATERIAL

Neben dem Körper ist die Sprache seit den 1970er-Jahren VALIE EXPORTs bevorzugtes Medium.

Die Werke, die im Kunsthaus Blaue Butter präsentiert werden, führen das pointiert vor

Augen. So hat die Künstlerin etwa für ihre Arbeit SCHRIFTZUG WIEN–VENEDIG von 1973 das

Wort „Schriftzug“ auf einen Eisenbahnzug geschrieben. Sie spielt hier nicht nur mit der

Bedeutung des Wortes, sondern nimmt auch auf den kulturellen und geografischen

Hintergrund, auf Mobilität und Zugehörigkeit Bezug – all das durch den simplen Akt des

„Beschreibens“ und den Werktitel. Schreiben und Zeichnen sind auch Themen (und Titel) von

VALIE EXPORTs Zeichnungen. In ihnen wird der Prozess, mit Sprache künstlerische Arbeit zu

erschaffen, nachvollziehbar. In den Videos, in denen sie Gedichte oder „Hauchtexte“ vor

der Kamera performt, wird die gesprochene Sprache zum künstlerischen Medium: EXPORT haucht

„Ich liebe Dich“ auf eine Glasscheibe, der Atem manifestiert sich als beschlagenes Glas.

Die Scheibe und das Kameraobjektiv (und dann wiederum der Monitor) scheinen ein und

dieselbe Fläche zu sein.

LANGUAGE AS MATERIAL

Aside from the body, language has been VALIE EXPORT’s preferred medium since the 1970s. The works presented at Kunsthaus Blaue Butter are a case in point. For her piece SCHRIFTZUG WIEN–VENEDIG of 1973, for example, the artist wrote the word “Schriftzug” on a railway train. Not only does she play with the multiple meanings of the German word “Zug” here (signifying a railway train as well as a stroke of script) but she also refers to the cultural and geographical background, to mobility, and a sense of belonging—doing all this through the simple act of writing and the work title. Writing and drawing also provide themes (and titles) for VALIE EXPORT’s drawings. They afford insights into the process of creating artworks with language. In the videos of her performing poems or “breath texts” in front of the camera, spoken language becomes an artistic medium: EXPORT breathes “I love you” onto a glass pane, her exhalation steams up the glass. The pane and the camera lens (and then the video screen) appear to be one and the same surface.

AKTIONSHOSE: GENITALPANIK

Die Aktion GENITALPANIK findet erstmals im April 1969 in einem Münchner Kino statt. Die

Künstlerin trägt eine Jeanshose, die im Schritt offen ist und ihr Genital unbedeckt lässt.

So geht sie durch die Sitzreihen, das entblößte Geschlechtsteil in Augenhöhe der

Kinobesucher:innen. Einige Zeit später lässt sie sich von Peter Hassmann in dieser Hose

und mit einer Maschinenpistole in der Hand fotografieren; die Bilder erhalten den Titel

AKTIONSHOSE: GENITALPANIK. Mit der radikalen Aktion im Kino will VALIE EXPORT die

Objektifizierung des weiblichen Körpers durch die Medien kritisieren. Die Waffe kommt erst

auf den Fotografien hinzu, um auf die Dringlichkeit des Anliegens und die feministische

Kampfbereitschaft zu verweisen.

ACTION PANTS: GENITAL PANIC

The GENITAL PANIC art action first took place in a movie theater in Munich in April 1969. Wearing a crotchless pair of jeans that left her genitalia uncovered, the artist sidled through the rows of seats, her exposed genitals at the eye -level of the movie audience. Some time later, she had Peter Hassmann take a series of photographs of herself wearing those same pants and holding a submachine gun in her hands; the pictures are -entitled ACTION PANTS: GENITAL PANIC. With her radical art action in the movie theater, VALIE EXPORT wanted to criticize the objectification of the female body by the media. The weapon was added only in the photographs to signal the urgency of the issue and the feminist willingness to fight.

Deborah Hazler

Deborah Hazler (geb. 1981 in Wien, lebt dort) erzeugt ihre Skulpturen, die sich stets mit

dem Thema der Vulva beschäftigen, durch Weben und Filzen, also klassische

Handarbeitstechniken. In ihrer PLEASURE ARMY, textilen Objekten aus Schafwolle in

unterschiedlichen Farben, empfindet sie die Form einer Klitoris nach, überdimensional und

kuschelweich. „Ich möchte mich nicht mehr schämen müssen, für meine Sexualität, für meine

Monatsblutung, für meine schon vorzeitig abnehmende Fruchtbarkeit, für meine bevorstehende

Menopause, für meinen Körper, für meine körperlichen Bedürfnisse, meine Sehnsüchte. Die

einzige Möglichkeit für mich, mich mit diesen anhaltenden Tabuthemen auseinanderzusetzen,

ist, über sie zu sprechen, sie in meinem künstlerischen Schaffen zu bearbeiten“, so

Hazler. Die Beschäftigung mit weiblicher Körperlichkeit, ihre Darstellung und der freie

Umgang mit ihr sind immer noch nicht selbstverständlich. Deshalb sind Deborah Hazlers

Arbeiten ähnlich radikal wie die von VALIE EXPORT als sie diese Themen in den

1960er-Jahren mit Wucht in den öffentlichen Diskurs brachte. Groß, bunt und laut, fast zum

Angreifen und Streicheln einladend, steht hier eine Armee von Lustspendern im Raum – ein

fröhliches künstlerisches Statement vor dem Hintergrund von VALIE EXPORTs ikonischer

AKTIONSHOSE: GENITALPANIK.

PLEASURE ARMY

Deborah Hazler (born 1981 in Vienna, lives there) uses weaving and felting, that is, traditional handicrafts, to create her sculptures, which always are about the theme of the vulva. In her PLEASURE ARMY series, textile objects of sheep wool in different colors, she recreates the shape of a clitoris, oversized and cuddly soft. “I don’t want to have to feel ashamed anymore, for my sexuality, my menstrual period, my prematurely declining fertility, my impending menopause, my body, my physical needs, my desires. The only way for me to deal with these persistent taboo subjects is to talk about them, to engage with them in my creative practice,” says Hazler. Addressing female corporeality, representing it and freely dealing with it is still not a matter of course today. That is why Deborah Hazler’s works are radical in a way similar to those of VALIE EXPORT, when she first brought these subjects to public discourse with a vengeance in the 1960s. Large, colorful and loud, almost inviting touching and stroking, an army of pleasure-givers stands in the room—a cheerful -artistic -s-tatement against the backdrop of VALIE -EXPORT’s iconic -ACTION PANTS: GENITAL PANIC.

Impressum

Verein zur Förderung

zeitgenössischer

Fotografie und Medienkunst

(e.V.)

Linzerstraße 16

4810 Gmunden

Österreich

ZVR: 1445731609

UID: ATU76881402

info@gmunden.photo

Initiatoren

Tom Wallmann, Felix Leutner

Kuratorin

Dr. Lisa Ortner-Kreil